Vår reports from Antarctica:

Cruise work is hard work! A week ago the actual scientific part of our cruise started, and we’ve been on our feet since. We deployed the Sail buoy and Sea glider just north of the sea ice edge and then headed into the ice. The “ice edge” is really a fitting term: you’re in open water, and suddenly, there’s ice all around. This depends on the wind and tides, but when we passed south it was a perfectly clear boundary, and very nicely marked the arrival of our science week. As soon as we passed into the ice penguins started to pop up, and we were all running back and forth on the bridge trying to spot them all. There are mostly Adelie penguins here, but we’ve spotted a few emperors as well, a few seals, one group of orcas, and another group of whales that we think might have been Minke whales.

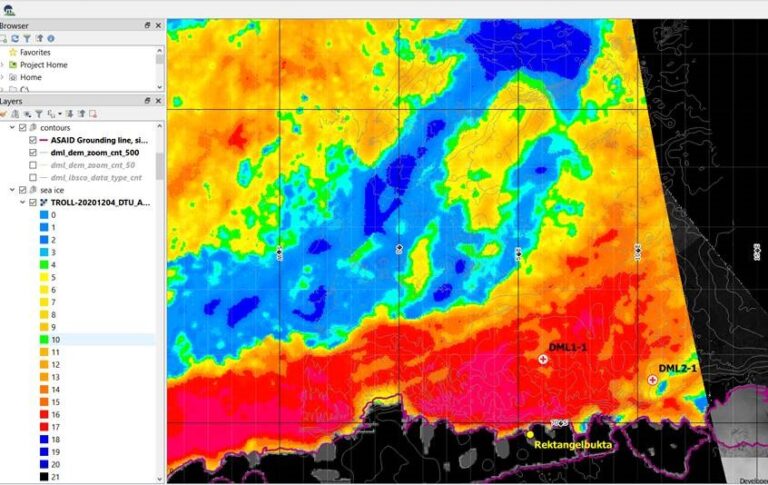

The sea ice conditions were a bit harsher than we’d hoped for and we had to change our route a bit, but it looks like we will cover most of the planned CTD stations and our mooring locations by the end. In addition, we got some measurements from a polynya just east of our ice shelf destination due to the detour we had to take.

On New Year’s Eve, we reached the ice shelf, and the crew anchored the ship to the ice front. To put it in perspective, we had to walk to the 9th floor to be on the level with the ice shelf. The crew from the Troll station arrived just before us and had already set up camp – it was a surrealistic sight to suddenly see people and “civilization” so far from anywhere, and after so many weeks without meeting any new people! As soon as the anchors were in place the unloading began, and we started an intense MSS profile protocol on the other side of the ship. As I’m most used to working with profiles from the other side of Antarctica and by far this close to an ice shelf, these profiles looked like nothing I’ve seen before. The software lets us look at the profiles real-time, and as we always do this profiling in pairs it’s been really interesting to discuss what might be happening in the ocean below us while taking the measurements. I’m growing very fond of this MSS instrument!

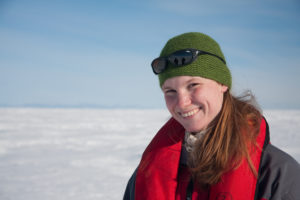

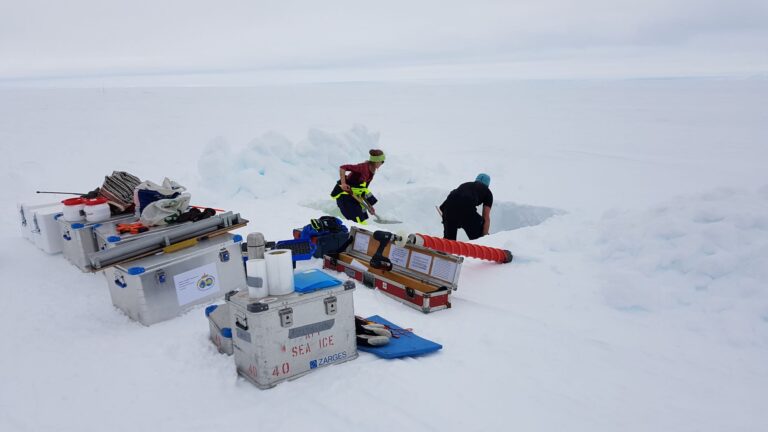

We our first day in 2021 on the sea ice itself. In Rektangelbukta, there is fast ice – sea ice that is attached to the coast – which makes it relatively stable and safe, and perfect for sea ice measurements. We packed our instruments and our lunch and set off on snow scooters with one of the guys from Troll who had assessed the safety some days before. As we arrived at our spot, we were welcomed by a team of very curious Adelie penguins and a serious-looking emperor penguin.

They lost interest in us when we were done with our lunch and started the process of digging a perfectly square pit in the snow to reach down to the ice. Our main task on the ice was to take ice cores to study temperature, salinity, biology, microplastics, and more, and to get these cores, the snow must be removed first.

When we pulled up our first core, the ocean flooded up through the hole, and suddenly our nice solid area was a shallow swimming pool. This happened because there is so much snow that it pushes the snow-ice interface below sea level. After pulling up all our ice cores we made a hole large enough to drop instruments through and got measurements of both temperature, salinity, some helium samples, turbulence, and also a special kind of ice called platelet ice, which forms in the ocean itself, not at the surface like normal sea ice. It was an extremely long day, and my face was burning and my eyes stinging when we got back to the ship from all the reflection in the snow, but also such a great day with lots of sampling methods I’ve never done before, the creativity of setup, and of course penguins and coffee breaks with the Antarctic sea ice and distant icebergs as the view. And I’ve done a cartwheel on Antarctica!

Now, we’re heading northward, and we’ve only got a few days left of scientific work. So far, the moorings have been deployed and recovered successfully, and hopefully, I’ll be able to say the same about the last mooring in just a few days. We continue with CTD stations and MSS profiles, water sampling, and mooring preparations. When all of this is done we’ll hopefully have time to do some bird and whale observations on our way back to Cape Town, besides packing up all our gear and tidying up the containers. On the way south we saw new species every day, and it would be interesting to see whether we see the same pattern on the way back. But for now, we focus on the work for the next few days and try to avoid any major problems.

Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius Photo: E. Darelius

Photo: E. Darelius