This blog post is an edited version that incorporated a lot of feedback I received on an earlier post over on my (Mirjam)’s blog “Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching”. If you have more to add, please let us know and we’ll update!

—

Going on your first research cruise is an exciting experience, and you are probably not quite sure what to expect from being out at sea on a ship with lots of new people for days, weeks or even months at a time. There are a lot of situations where you might not be quite sure how to behave, especially since the ship you are joining might be crewed with people from a different culture. And even if it isn’t — it’s like going on a sleep-over at your friend’s house as a kid: You never quiiite know what to expect, whether you’ll like what’s for dinner, and what polite behaviour might look like in that family.

Before we go into the actual “rules”, the main thing to be aware of is that while you are onboard the ship for what feels like a long time, that is nothing compared to how long the crew stays on the ship. The ship is their home for half the year every year, and you are a guest in their home. As Ilker Fer put it on Twitter: “Don’t forget that while this might be a rare and intense fieldwork for you, the ship is a daily workplace and home for the crew. Hard working and ambitious scientists and students tend to forget this.”

That said, it’s not immediately obvious what all of this means in terms of concrete behaviour. What’s considered polite in some cultures might be very rude in others. So if in doubt, just ask!

It’s ok (and even encouraged!) to ask if you are unsure of anything

Asking is actually the top 2 answer that our favourite sailor gave us in response to what students should know about how to behave on a research ship. Here are his top 3:

- Always be yourself. If you pretend to be someone you are not, people will find out soon enough anyway.

- Just ask. There are no stupid questions and sometimes having asked about something you are not sure about on a ship might end up being crucial for your safety.

- Be friendly. ’nuff said.

He says that’s all people need to know about how to behave at sea. While I kind of agree, those three rules are kind of … vague. But there are some “rules” (it’s more like guidelines, anyway, and bonus points if you got the movie reference) for what we have found works well on a research ship.

Etiquette on a research ship

Meal times

While meal times are often given as a one-hour time slot and you might think that means you can drop in at any time during that one-hour window, that’s not how things work on a ship. Usually, this one-hour window is meant as two 30min windows for people working on different watches. In between those two windows, the first group of people has to get out of the mess (not the messmess, the room where food is served on a ship is called the mess), the tables have to be cleared completely, and food refilled. So to be polite towards the people making sure you get fed, it’s good advice to arrive on time for your feeding window and don’t linger too long after you are done eating, so they can get the room ready for the next group or finish off that meal to move on to other tasks. If people start wiping the tables, it’s a clear signal that you should find some other spot to lounge in. If, however, you have to be late for a meal due to work reasons, everybody will be happily accommodate you and make sure you leave happy and satisfied. Just don’t push it without a good reason.

Thank the cook & galley personnel

This should go without saying, but if someone puts a nice meal on the table in front of you, say thank you. If the food was delicious, let the cook know. “Takk for maten” is something that comes pretty much automatic out of every Norwegian’s mouth, but whatever your background, I think everyone should adopt it on a ship (and maybe also at home ;-)).

Don’t complain about the lack of fresh veggies and fruit

Amelie Kirchgaessner shared this one with us on Twitter: “Don’t moan about the lack of fresh fruit and vegetables. When there is some, be grateful, and eat it, even though the banana may bend the wrong way or have brown spots. Also, consider those who may be onboard for longer, ie have a stronger craving for freshies.”

If you drink the last drop of coffee, start brewing a new pot

This rule has actually been rejected by my favourite sailor after it was put forward on Twitter — while on some ships the polite thing might be to start brewing a new pot, on that particular ship the crew would prefer you let them know there is no coffee left so they can brew it themselves. Which goes back to asking what kind of help is wanted and needed before “helping”.

“No work clothes” means “no work clothes”

On ships, there are usually areas that you are supposed to not walk through, or hang out in, wearing work clothes. That’s because the ship is the crew’s home for long periods at a time (and also yours while you are at sea), and keeping a home nice and tidy is a big part of making it feel like home. And also it’s just mean to make the cleaning crews do extra work just because you couldn’t be bothered to change out of your fishy boots.

When you leave your cabin, leave the door open

Leaving the door to your cabin open when you are not in it makes it a lot easier for the crew to get their work done. They won’t knock on your door when it’s closed because they are respecting your privacy and your sleep, but they want to empty your trash, put new towels in your cabin, clean, etc.. The larger you make the time window for them to do that by just leaving your cabin door open, the less they have to organize their work day around catering towards you.

Be quiet on corridors, people are sleeping

You are not the only one going on watches (and even worse — just because you don’t go on watch doesn’t mean that other people are not), so be considerate of other people’s sleep. While it sucks to be tired as a scientist on a ship, other people have safety-relevant work to do (and also just live on the ship for many weeks at a time) so they should definitely be able to get the sleep they need.

Also consider whether you really have to go to your own comfy cabin and your own comfy toilet during your watch if you know people are sleeping in the cabins next to yours. Cabin doors are loud, vacuum toilets are really loud, but walls between cabins are more like paper than like actual walls. If you can avoid making unnecessary noises that might wake up other people by just going to a common restroom, you should probably consider doing that.

Respect people’s privacy

There is not a lot of spaces where you can hide on a ship to get your alone time when you need it. So do not enter other people’s cabins unless invited, and don’t go knocking on their doors unless there is a good reason. People will leave their doors open if they are open to communications, if the doors are closed it means you should leave people alone unless you really have a good reason.

Also the cabins are the only private spaces people get. If you wouldn’t go into someone’s bedroom in their house without explicit permission, why would you do it on a ship?

And as Hugh Venables points out: “Everyone relaxes and misses home differently. Know when to be professional, when to be silly, when to be the butt of a joke, when to answer back and when to leave alone”

Access to all areas?

Usually, you are free to go pretty much wherever you like on a research ship (except, as I said above, into other people’s private spaces). If areas are off limit (like for example the engine room or spaces where food is stored and prepared), you will be told that. But it’s still good practice to ask whether it’s ok to hang out. For example, in heavy weather or very tight straights, people on the bridge might prefer to not having you hanging around and possibly obstructing their work. And while they will tell you that, just asking whether it’s ok to be there makes it less awkward for everybody involved. Same if you visit other scientists in their labs, or the crew in the trawl mess — sometimes it might not be immediately obvious to you that people are concentrating on their work, even though they might look like they are just chilling, and that you are getting in the way of that. Or even just getting in the way of people chilling when they need to do that.

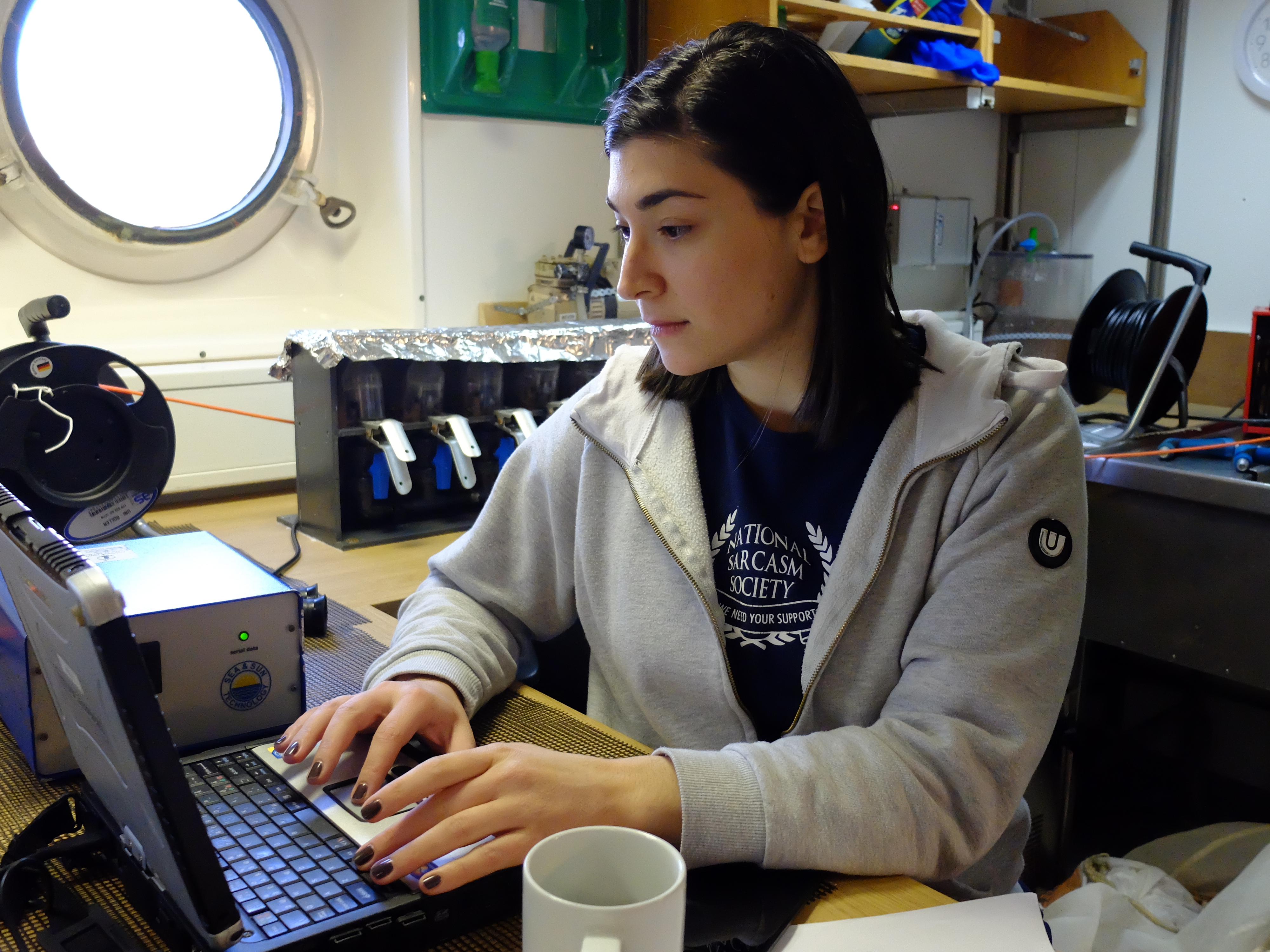

Be on time for handover between watches

Even if you are told that your watch runs from midnight to six in the morning and from noon to six in the evening, that doesn’t mean you show up at midnight and noon sharp. It means that the other watch wants to be able to leave at midnight and noon sharp, so handover should have happened before that time. It’s good practice to show up at least 5 minutes before watch changes.

Be on time for stations

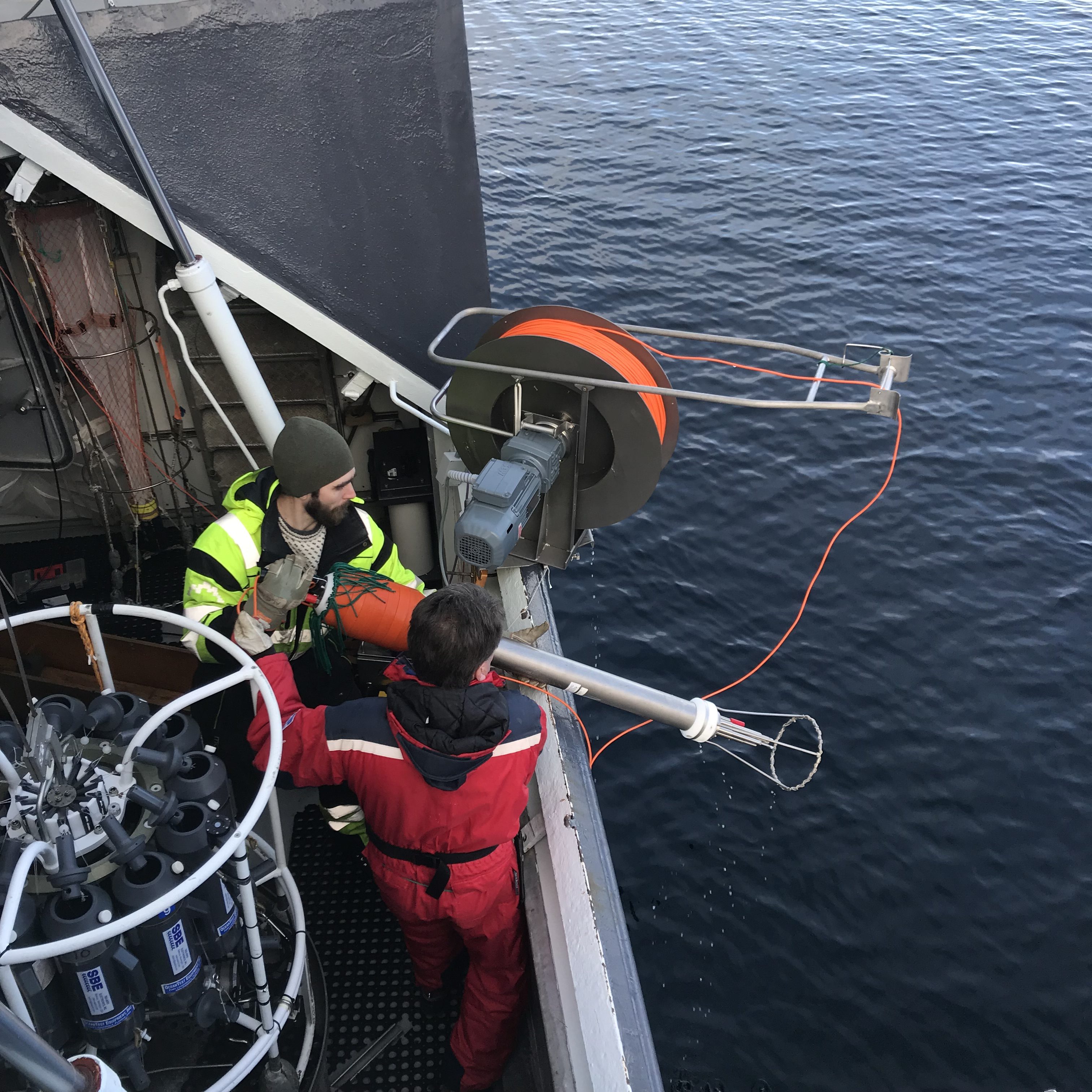

People not being ready to start working when the ship is on station is a pet peeve of mine. Ship time is very expensive, so spending it on waiting for someone who wanted to get a hot chocolate right when the ship is ready to take measurements (instead of looking at the screen that shows you the navigation data of the ship, including ETAs of stations etc and getting it while there still is plenty of time) is a very bad use of taxpayers’ money.

Also be aware that there are a lot of people waiting for you once the ship is in position to start measuring: The officers on the bridge, the deck crew possibly standing outside in cold, windy, rainy weather, your other scientist colleagues. Not very good for the general mood if they unnecessarily have to wait for you.

Be proactive in offering help

This “rule” was suggested by Kim Martini: “Be proactive in offering help, but [very importantly!] always ask first because sometimes what you think are the right steps just may create more work”. And we 100% agree with both parts of this rule! Do offer to help, always, but always make sure the other person tells you what exactly they want done. And Kim adds “definitely offer help when loading and first getting on board. You never know if you get seasick later in the cruise and need someone to help you!”

It’s cold and in the middle of the night for the crew, too

Just because they might not let you see it doesn’t mean you are the only one that is tired and cold and feels cranky. I guess this goes back to rule no 3: Always be friendly and considerate of the people around you…

And as Ian Brooks put it on Twitter: “When the deck crew ask what time you need to put that bit of kit over the side, the correct answer is just AFTER coffee break!” And Joana Beja points out: “On my last cruise we found that the crew had had their dinner “on deck” so as to not delay work… none of us noticed and they didn’t tell us! They were great but it only happened once and we made sure we told them how thankful we were. and that it wasn’t required at all.”

Radio communication is safety relevant

Having fun with a radio is fun, but there are a lot of people working on the bridge or the deck that have to listen to everything you say on the radio. So if you try to be overly funny, you might end up annoying people, and worse, making it more difficult for them to do their job and keep you safe.

Don’t discuss safety issues

If the crew tells you to wear a life vest on top of your floatation suite (that is certified as being sufficient in itself) when going on a small boat trip, or a helmet when taking water samples, just wear it. In the end they are the ones that know better, and they are the ones responsible for your safety so even if they are, in your opinion, unnecessarily cautious, they are just doing your job making sure you are safe. So even if it seems unnecessary to you, if they tell you to do something, just do it.

If plans change, let people know early on (and maybe explain why)

Changing your plans might require a lot of work on the crew‘s part — putting together different instrumentation, rearranging equipment on deck, changing out winches, all kinds of stuff that you might not be aware of. So if you happen to change your plans, let them know as soon as possible so it creates the least amount of stress for them.

Also offer to explain the scientific reasons why you now think the new plan is better than the old one. In my experience, in general the crew is really curious about what they are helping you achieve (and what you really could not achieve on your own if they weren’t there to help!), and really appreciate if you let them in on what you are doing for what purpose. And also what the outcomes are!

Don’t make a cruise longer than it has to be

Even though it might be fun for you to extend your cruise for a couple of extra hours just because it’s so nice to be at sea and you feel like you payed for that day of ship time anyway, don’t change arrival times back in port on a short notice without a really good reason. The crew might have made plans with their family and friends whom they don’t see very often, that they will have to cancel. This is going to make a lot of people not very happy!

And this goes without saying: Don’t extend a cruise just to get the extra pay you get for every day you spend at sea. While I find it hard to imagine people actually do that, I have heard from so many different crew that they think a lot of scientists do that, that it’s hard to ignore the possibility that it actually happens, and quite often at that.

Etiquette on a research ship: Anything to add?

If there is anything you think should be added, please let us know and we’ll happily edit this blog post!

Guest blog by Karen Assmann

Guest blog by Karen Assmann

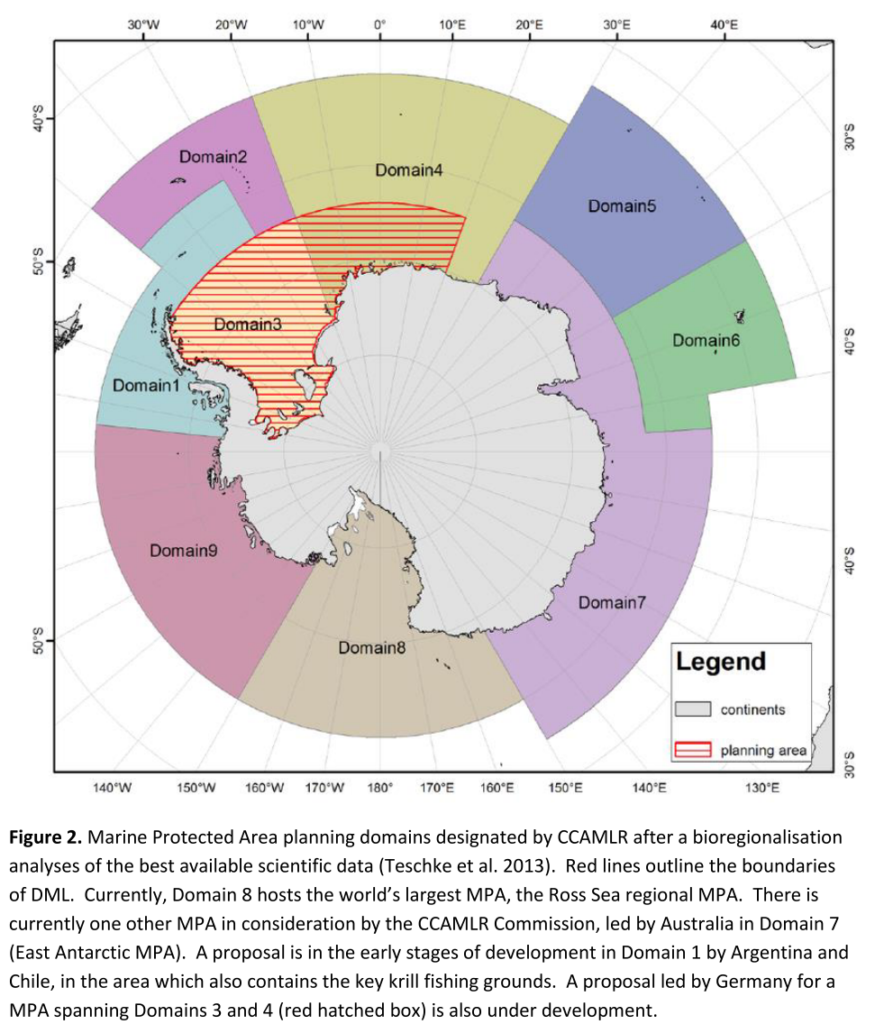

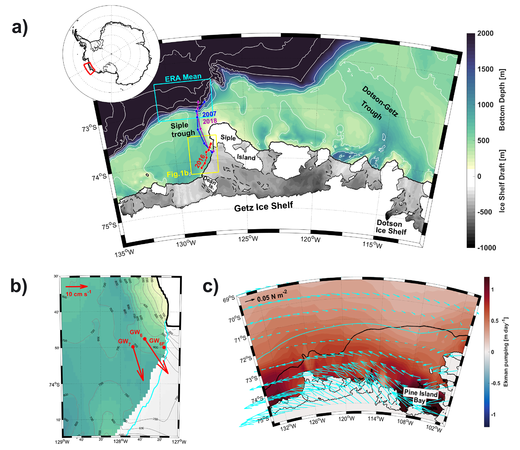

This is the Getz ice shelf in the Amundsen Sea! Our moorings were placed within the yellow Box, and the observed mean current is shown in (b). Panel (c) show the mean wind field.

This is the Getz ice shelf in the Amundsen Sea! Our moorings were placed within the yellow Box, and the observed mean current is shown in (b). Panel (c) show the mean wind field.