This semester, Kjersti is teaching GEOF105 under very difficult circumstances. While much of the class happens virtually, both the mandatory lab experiments and the student cruise could (luckily!) happen. So we could also do our planned Instagram-takeover of @realfaguib‘s account!

For a week, we used Instagram’s “Story” function — pictures that can be annotated and that vanish after 24 hours (not completely, you can still see a whole week’s worth of posts here if you like) — to give little glimpses of what it is like to do experiments on rotating and non-rotating tanks, and to be on a research ship for the first time.

Instagram Stories turned out a really good tool for that, for example because we could insert gifs to illustrate concepts. Above, for example, the football above the rotating tank is spinning around its own axis, while the one above the non-rotating tank is not in motion.

And of course people like seeing pictures of cruises and colorful instrumentation!

After some initial hesitation, we were lucky enough that Ide and Stephanie took over our take-over and helped make it even more authentic & fun. Thank you!

Watching their story and seeing student cruises through students’ eyes was really interesting!

With between 700 and 1000 views for each image in the story (plus some really good questions related to what we do at sea!), we feel that we had a really successful week in terms of reaching current and prospective students with interesting stories about the issues at heart of GEOF105.

That said, the only thing left to say is a huge “thank you!” to captain and crew (who, after lunch break, swapped roles) of the research ship Hans Brattstrøm, and to @realfaguib for giving us the opportunity!

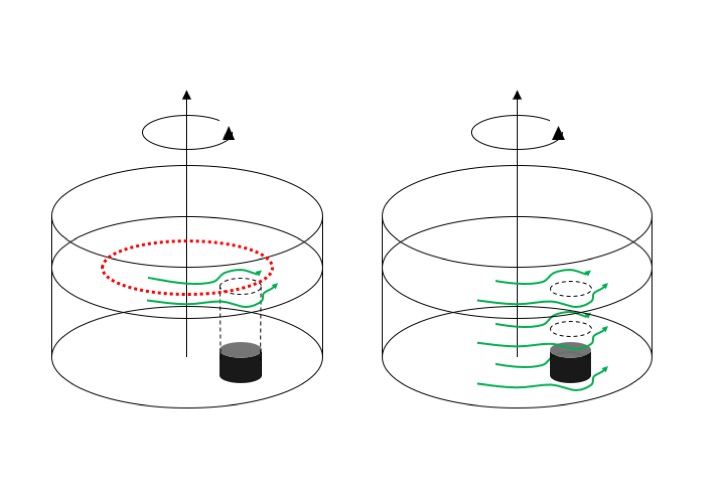

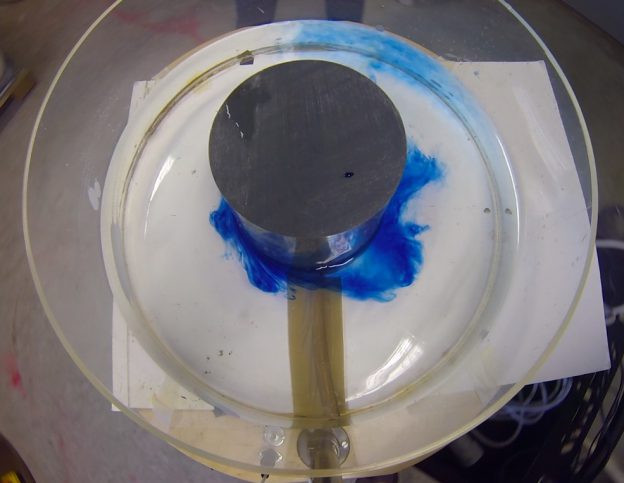

I wonder if the cashier reacted to my somewhat strange shopping list last Saturday morning: 1 kg of salt, three kilos of ice and a bottle of food coloring. Had he asked, I’d gladly have told him that I was on my way to “

I wonder if the cashier reacted to my somewhat strange shopping list last Saturday morning: 1 kg of salt, three kilos of ice and a bottle of food coloring. Had he asked, I’d gladly have told him that I was on my way to “