Written by Svenja Ryan

We have already written about the article of Elin, where she shows that for the first time pulses of warm water have been measured in the vicinity of the ice front. This means that under certain conditions the warm water, can travel several hundred kilometers south along the eastern side of the Filchner depression, i.e. our trough. Of course everyone wants to know whether the trough provides a permanent pathway to the south for the warm water, which would be a big threat to the Filchner Ronne Ice Shelf.

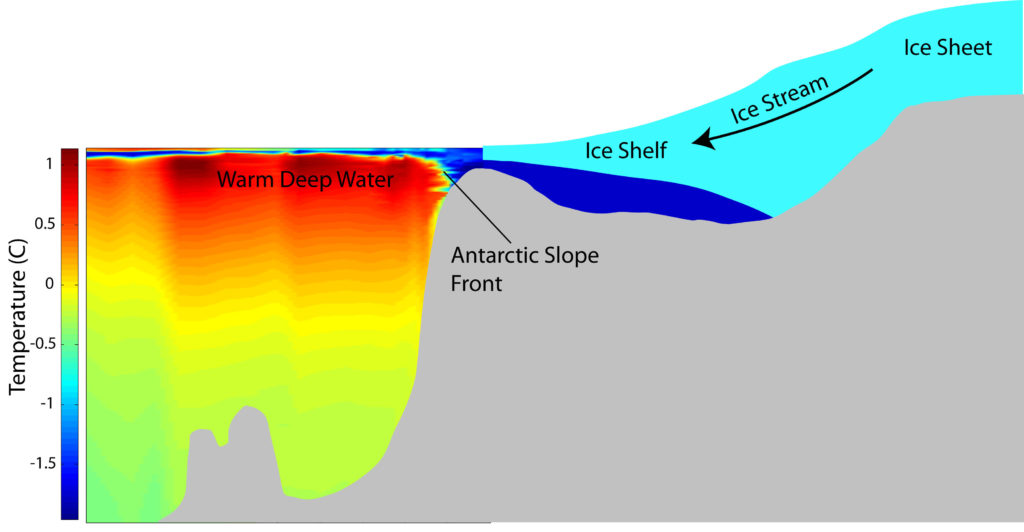

We will come back to this problem in a little while but first have to explain something that we call ‘Antarctic Slope Front’. I think most of you are familiar with weather fronts, where for example cold and warm air meet. The same things exist in the ocean, when warm and cold or light and dense water masses encounter each other. This exactly is the cast almost all the way around Antarctica where fresh and cold water is found on the continental shelf and warm water (CDW/WDW) flows along the continental slope. The resulting front is the Antarctic Slope Front (ASF) as show in Figure 1. The depth of this front determines whether the deeper warm water can access the continental shelf or not. During our experiments we will also introduce a density difference at some point by have saline water in the tank and a fresh source.

Several mechanisms can influence the ASF such as the wind and the upper-layer hydrography, both having a strong seasonal cycle. Therefore, it is no surprise that the ASF depth also varies seasonally and it has been shown by various authors, that it is shallower in summer, favoring on-shelf flow of warm water and deeper in winter, reducing the access for warm deep water.

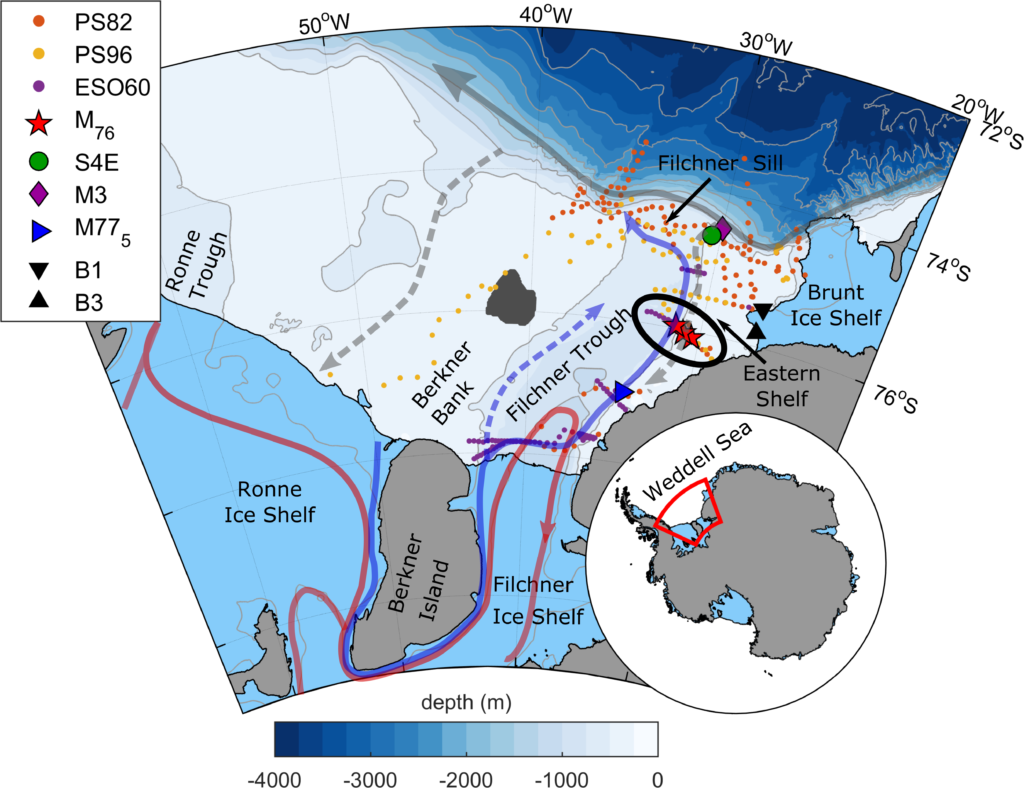

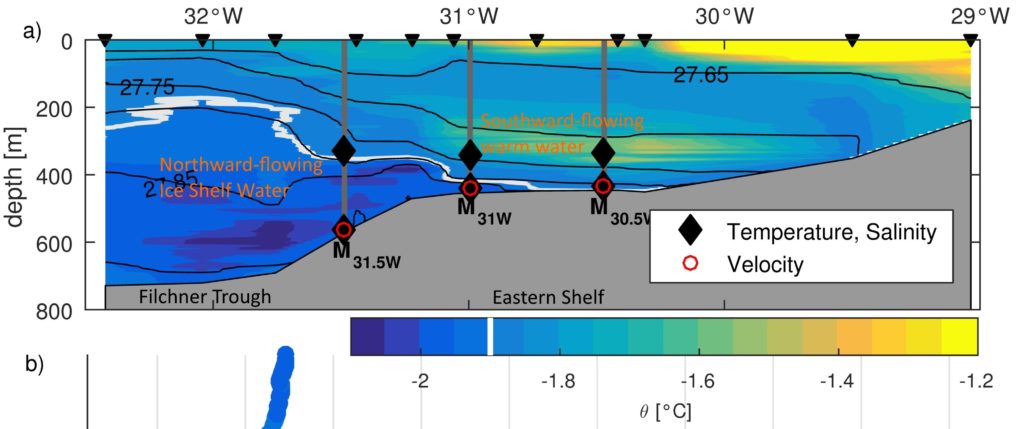

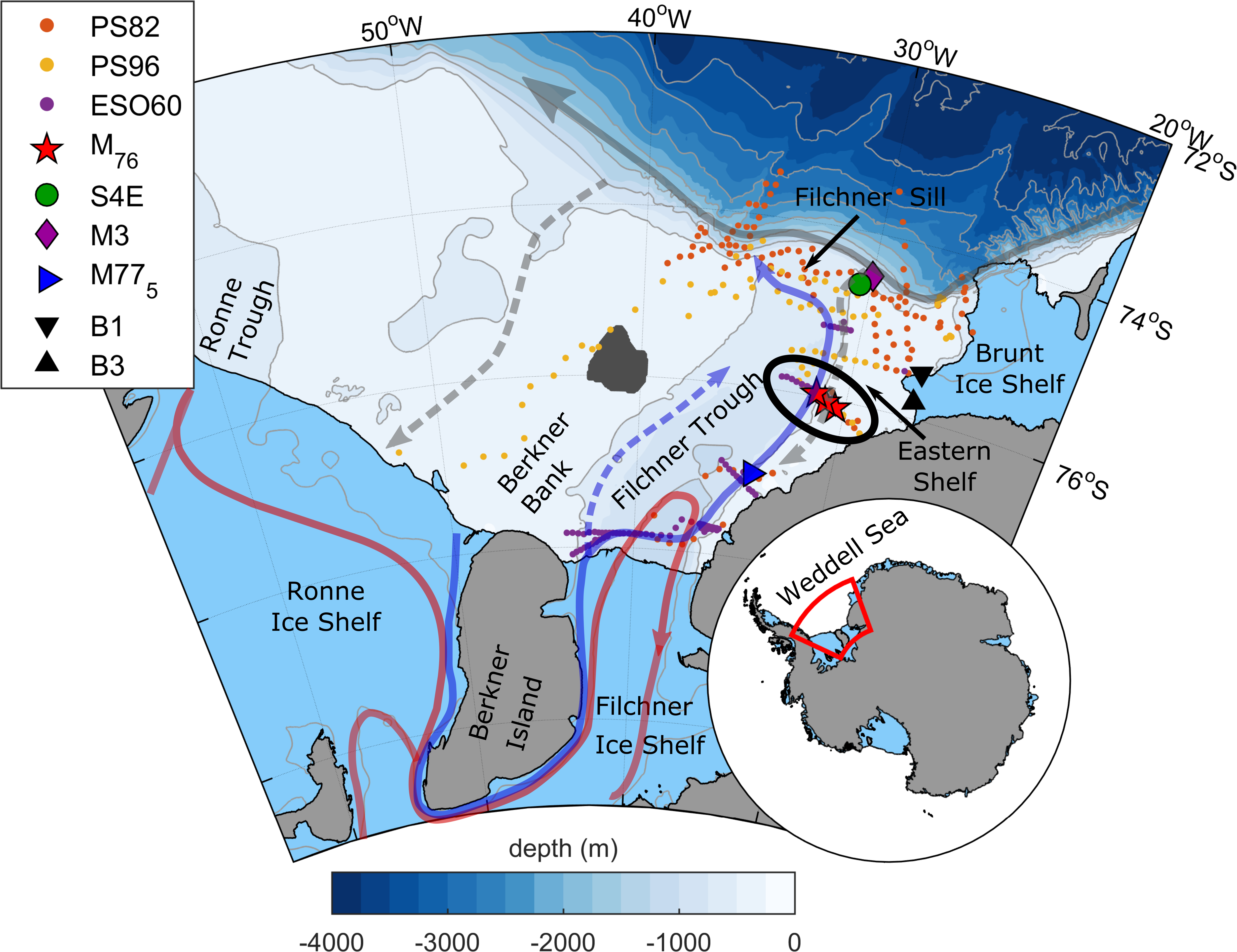

So, now we know that there might not be warm water available at the shelf break to flow toward the ice front at any time. Another important factor is whether the circulation on the continental shelf would transport the warm water toward the ice front all year around. Hence, we took the German ice breaker RV Polarstern and went to the Filchner region to put some more instruments in the water and I analyse the data in my recent publication (Ryan et al., 2017). The map in Figure 2 should sort of look familiar to you now as it similar to the one in a previous article. You can see the coast to the right, then the continental shelf (Eastern Shelf) that opens up and the trough cross-cutting the shelf toward the Filchner Ice Shelf. We put moorings, i.e. a long upright floating lines with instruments at different depths, where the three red stars are on the map and left them there for two years. It is the eastern flank of the trough, where the warm water (dashed gray arrow) was observed to flow south adjacent to the northward flowing cold water, called Ice Shelf Water, emerging from underneath the ice shelf (blue arrow). You can see in Figure 3 how this looks like in a temperature section and where we took our measurements. You might wonder, why we did not put instruments shallower than 300m. If we did, we would risk these instruments to be ripped off by ice bergs, and there are plenty of them around. We found that there is only a certain period in summer-autumn, where we detect southward flowing warm water at our moorings. In winter, the water column becomes very cold and uniform with temperatures close to the surface freezing point and there is no southward flow anymore. So for now it seems like there is no permanent pathway for the warm water toward the Filchner Ice Front. However, in a warming climate the conditions on the continental shelf in winter could change, with warmer atmospheric temperatures and reduced sea ice production. The latter, could also reduce the production of ISW which is currently filling the whole trough and is sort of ‘blocking’ the warm water from entering the centre of the trough.

Of course we do not have winds, ice etc. in our tank experiments but there is still so much more to be understood on how the warm water can be transported on the shelf and how for example the ASF changes in the vicinity of a coastal trough. Most measurements or time series are too short or too scattered in order to really understand fundamental processes and mechanisms, this is where a big rotating tank can help us!

—

Ryan, S., Hattermann, T., Darelius, E., & Schröder, M. (2017). Seasonal Cycle of Hydrography on the Eastern Shelf of the Filchner Trough, Weddell Sea, Antarctica. Journal Geophysical Research – Oceans. http://doi.org/10.1002/2017JC012916

2 thoughts on “A bit more about real Antarctica”

Comments are closed.