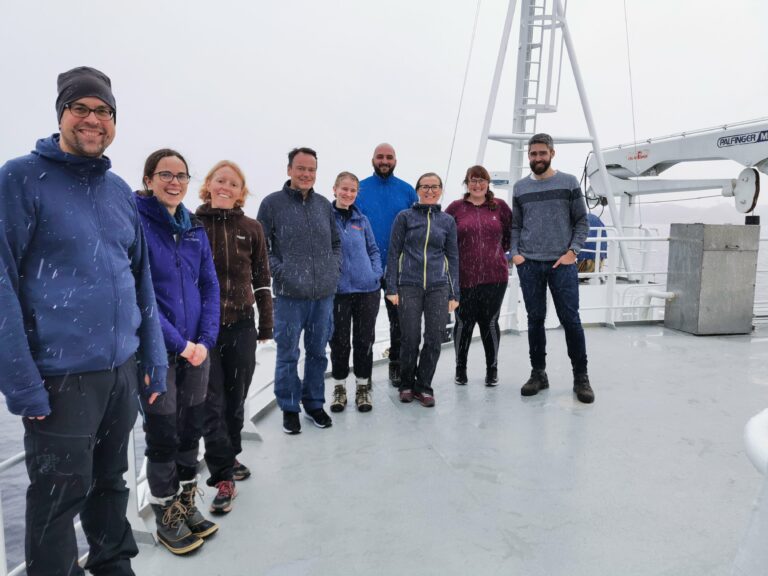

Snow, rain, and wind… the weather forecast was everything but promising when I left Bergen harbor together with a team of excited scientists last week onboard Kristine Bonnevie, our research ship. She headed northward towards the nearby fjords “Lurefjorden” and good old “Masfjorden.” The gear on deck was slightly different from what I am used to; the familiar mooring buoys and instruments boxes were accompanied by what I soon learned is called a “multi-corer” and a “gravity corer.”

These strange-looking creations are designed to collect mud – or sediments – from the ocean floor. As the sediment deposits chronologically, one layer at a time, they form an archive of the past. The deeper into the sediments you dive, the further back in time you go. Remnants of marine life deposited on the bottom – microscopic shells from foraminifera, for example – have incorporated information about the ocean properties at the time when they were living. Advanced bio-geochemical analyses can bring that information back. Or you can identify the shells – different species thrive in different conditions, some when there’s a lot of oxygen in the basin, others when there is little. If you know how to interpret the signals – you can turn what to most people looks just like mud into a historical record of fjord hydrography and learn how the oxygen concentration in the fjord basins has changed in time. To me, mud is mud, but luckily, we had Irina, Stijn, Agnes, and Dag-Inge, on board. They are paleo-oceanographers; they know how to turn mud into exciting science!

I almost forgot Mattia – our fresh PhD-student who arrived a couple of weeks ago to chilly and rainy Bergen from sunny Sicily. He will be working with the mud for the next three years.